In Wayland, we must build on ruined habitat—not on the ecosystems we can’t replace. Residents live in one of the most beautiful towns in Massachusetts. Our identity is shaped by meadows, wetlands, forests, and the Sudbury River—natural assets that make Wayland unique and profoundly worth protecting.

Wayland also faces mounting housing pressures. As we discuss how to add more homes, it’s critical to acknowledge a simple ecological truth: where Wayland builds housing matters.

Most of Wayland’s suburban yards are already ruined habitats. They look green, but ecologically they are nearly barren, but the town’s remaining natural areas still function as living ecosystems. When these areas are developed, the loss is permanent.

Wayland’s large lots result in vast expanses of turf lawn, scattered non-native shrubs, and fragmented patches of forest. Lawns are the largest “crop” in Wayland, yet they support almost no insects, provide minimal food for birds, and sever the wildlife corridors that once crossed these same neighborhoods. Many of the ornamental plants we’ve installed—burning bush, barberry, Japanese maple, forsythia—are attractive but biologically empty. Much of Wayland’s residential land is already ecologically degraded.

Contrast this with the sensitive areas that define Wayland’s natural heritage: the Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, the Sudbury River floodplain, Pod Meadow, Heard Farm, Greenways, and the woodlands that form our conservation network. These are places where ecosystems still function—where migratory birds feed, amphibians breed, and pollinators thrive. Clearing these areas for development would mean losing biodiversity that cannot be restored.

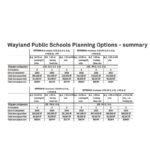

If we must build housing—and we must—then we should build it on land that has already lost its ecological value. Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), allowed statewide, are exactly this kind of responsible development. They are built on existing lots—above garages, in attics, in basements, or as modest backyard cottages. They require no forest clearing or new roads. Wayland residents are already embracing this approach: the town has received eight ADU applications since the new law went into effect.

ADUs allow homeowners to add needed housing while keeping their yards intact. Research by conservation biologist Dr. Doug Tallamy shows that small changes—adding a native tree, planting blueberry or viburnum, reducing lawn area—can transform biologically empty yards into a living habitat. A single native oak can support over 500 species of caterpillars, a food source essential to nesting birds.

Wayland faces a dual challenge: housing affordability and environmental protection. The solution is not to halt growth. It is to place new housing where the environmental harm is the smallest.

Jean Milburn

Concord Road