By The Wayland Post Staff

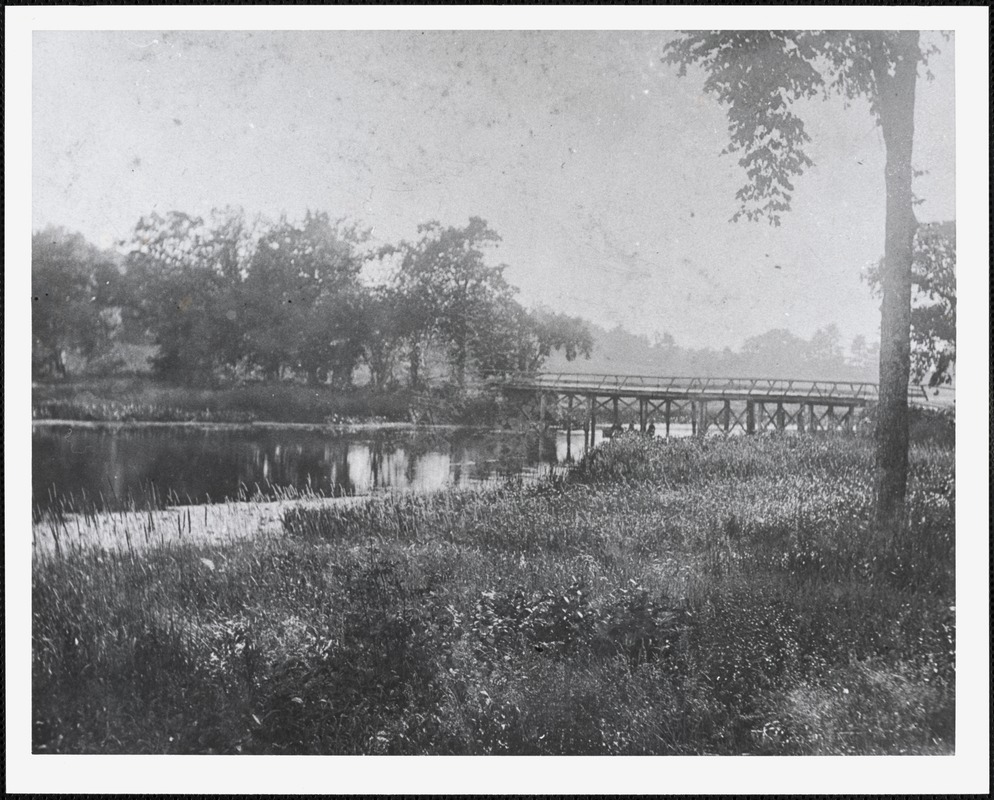

On warm evenings, long after commuters have rushed home, Sherman’s Bridge becomes something quieter. The river falls still, the marsh grass darkens, and a narrow wooden deck rattling and uneven by daylight turns into a silhouette over the Sudbury River. Walkers pause to watch the last color drop behind Weir Hill. Teenagers lean on the railing to look for herons. Photographers hope the northern lights will glow faintly above the refuge.

It is only a simple wooden span. But for nearly three centuries, the 112-foot-long Sherman’s Bridge has stood where nature, history, and community converge. In recent months, it has also become the center of one of the region’s most complex civic debates: how to repair and preserve a wooden bridge that is at once a neighborhood treasure, a recreational gateway, a transportation choke point, and a point of tension between two towns, two public works departments, and many competing visions of the future.

Any discussion of how to “fix” Sherman’s Bridge – its decking, guardrails, traffic patterns, or role in regional mobility – begins with this: Sherman’s Bridge is not just infrastructure. It is a place layered with Indigenous history, colonial settlement, river ecology, local activism, modern planning, and countless personal stories. Its past is long, and it is very much alive in today’s arguments.

An Ancient Crossing: Weir Meadow Before the Bridge

Long before anyone named Sherman lived on the riverbank, the Great Meadows were part of an Indigenous landscape of food gathering, fishing, and travel. The high ridge now known as Weir Hill was described in Alfred Sereno Hudson’s “1891 Annals of Sudbury, Wayland and Maynard” as “a point of the river where… at low water the river can be forded,” with rare firm banks on both sides.

In the mid-20th century, longtime resident Henry Kolm documented oral histories of the Warren family, whose ancestors had lived on the riverbank since the early 1800s. In his memoir, Kolm described a hand-drawn map showing an “Indian weir” at the foot of the hill, a burial ground near Pantry Brook, and “Weir Meadow Path,” which followed the esker ridge now called Castle Hill Road a main north–south Indigenous route long before Route 126 existed.

Archaeology students and residents have found charred hearth stones, stone points, and pestle fragments along the meadow. These discoveries tell a larger story: the Sherman’s Bridge area was not simply a crossing, but an Indigenous cultural site, a place where fish ran, where food was prepared, and where travelers moved through the valley long before European settlement.

Building the First Wooden Bridge: 1740s

The first wooden Sherman’s Bridge was constructed around 1740. Residents John Haynes and John Woodward agreed to allow a two-rod-wide way through their land if subscribers funded the bridge. The span about 100 feet long with 25 rods of approach roadway bridged the river between Sudbury and what was then East Sudbury (now Wayland).

By 1795, the crossing was shown on one of the oldest surviving maps of Sudbury as “Sharman’s Bridge.” It had already become essential to moving farm goods, timber, and hay between the towns.

From 1785 through 1924, Sudbury Town Meeting repeatedly voted funds to repair or rebuild the bridge, underscoring its importance and its fragility. Wooden bridges built in floodplains did not last long. They had to be tended, patched, and occasionally replaced entirely.

Thoreau’s River: The Meanders of 1851

Henry David Thoreau paddled past Sherman’s Bridge in 1851 and described the river’s wild serpentine path:

“Now commenced the remarkable meandering of the river… Landed at Shermans Bridge. An apple tree made scrubby by being browsed by cows.”

The meadows, dotted with haycocks, stretched south toward the Causeway. Farmers from Waltham and Watertown mowed these meadows seasonally, part of a river economy that persisted well into the 20th century.

Thoreau’s notes capture what remains recognizable today: a place where the river slows and wanders, the hills rise gently, and the world feels slightly older.

The Industrial River and the Conservation Century

The Sudbury River has not always been pristine. In the early 1900s, carpet mills at Saxonville and dye works upstream discharged waste into the river. Kolm recalled that only catfish survived; other species had been killed by pollution. By the 1950s, after legal battles, the river was declared safe again for swimming.

But then DDT spraying began. Residents described sequential disappearances: swallows, night herons, bitterns, even blue herons. Only after Silent Spring and environmental advocacy by groups like Sudbury Valley Trustees did wildlife begin to return though some species, like swallows and night herons, never fully recovered.

These ecological shifts foreshadowed the modern conservation movement. In the early 1960s, federal and state governments purchased large tracts along the Sudbury, Assabet and Concord rivers to form the Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge. The Sherman’s Bridge landscape became protected habitat marsh, meadow, floodplain, and migratory bird corridor.

The valley saw another environmental showdown in the 1970s, when Boston Edison proposed high-voltage transmission lines down the river corridor. After years of hearings, lawsuits, and grassroots organizing, the utility was forced to bury the lines instead of erecting towers. It was a critical victory for what was becoming a nationally recognized river corridor.

The 1971–72 Agreement: Straightening the Road, Preserving the Bridge

In 1971, Wayland sought to straighten Sherman’s Bridge Road to improve safety and sightlines. Neighbors feared that a straighter approach would increase speeds and create pressure to widen the bridge.

Negotiations followed. Fourteen property owners agreed to give the town approximately 14,139 square feet of land for no monetary compensation. In return, town officials agreed to preserve the rural, narrow character of the bridge and road. The agreement included:

- An 18-foot pavement limit on Sherman’s Bridge Road

- A permanent 2½-ton bridge limit

- Preservation of the bridge’s wooden aesthetic

- Use of the narrow bridge as a natural traffic-calming regulator

- A ban on accepting state money for the bridge or road

The article passed at the 1972 Annual Town Meeting. In 1991, Maurice “Maury” Stauffer wrote a letter to the Wayland Historical Commission that explicitly outlined the terms and intent of the agreement. A June 24, 1971 Town Crier article also documented the compromise, confirming its public understanding.

The agreement was never rescinded and remains, in the view of many residents and historians, binding an obligation rooted in land transfers and community promises.

The 1987–1992 Historic Documentation and Timber Reconstruction

By the late 1980s, the existing wooden bridge (a successor to many earlier versions) was deteriorating. In 1987, a Massachusetts Department of Public Works historic bridge specialist submitted a comprehensive MACRIS inventory form noting that Sherman’s Bridge was part of the refuge landscape and historically significant.

In 1990, the Wayland Historical Commission urged “minimal design changes,” emphasizing that a historic crossing deserved a sympathetic reconstruction.

The bridge was closed in 1989 for safety reasons and rebuilt in 1991–92 using native timber under federal and state programs, as reported in The Boston Globe and the Town of Sudbury Annual Report. The design preserved the visual simplicity of the structure low profile, wooden deck, wooden rails, and unobstructed river views.

A 1992 MACRIS filing titled “Sherman’s Crossing of the Sudbury River” formalized its significance as a heritage resource for both towns.

By the mid-2000s, the bridge was featured on the cover of the Sudbury Reconnaissance Report and designated a “Priority Heritage Landscape,” placing it alongside the state’s most culturally significant river crossings.

A Bridge with a Constituency: 2015 Debates and Renewed Concern

By 2015, the bridge’s deck had begun showing its age. Planks loosened, bolts pulled up, and the deck surface became irregular.

That year, residents voiced early concerns after the Wayland DPW signed a $60,780 design contract without public discussion. A Wayland Town Crier article from August 20, 2015 documented the growing debate, including testimony from resident Kurt Tramposch, who described the bridge as “a window on the wildlife refuge… the second oldest wooden bridge in the state… a meeting place over centuries.”

Residents emphasized two values that continue to define today’s debate: Keep it wooden. Keep it slow.

In 2016, Sudbury applied for $4.4 million to replace the bridge with concrete. That proposal did not advance, but it sharpened awareness: the bridge could be vulnerable to top-down redesigns if residents were not vigilant.

A Bridge That Slows You Down: Recreation and Road Safety Recreation

Sherman’s Bridge today supports six major forms of passive recreation:

- Boating and canoeing: Two gravel ramps on the Wayland side offer one of the few launch points along the entire Sudbury River.

- Fishing: The northwestern walkway is a favorite spot for anglers.

- Cycling: It is the only non-numbered-road river crossing for eight miles, a critical link between Pelham Island Road and Concord. Strava heat maps show cycling volume comparable to Routes 27 and 126.

- Walking and wildlife viewing: The vantage over the Great Meadows is unmatched.

- Birdwatching: Approximately 100 species have been recorded from the bridge and approaches.

- Stargazing: The stretch has some of the darkest skies in Wayland.

Road Safety

Sherman’s Bridge Road and Lincoln Road are among the hilliest and most curved roads in Wayland and Sudbury. Crash data from 2015–2025 show repeated collisions near the bridge. Wayland police speed studies from June 2023 revealed:

- Average speeds: 35–37 mph in a 25 mph zone

- 85th percentile: 42–43 mph

- Top speeds: 60 mph “about a car a day” reaches that speed

Meanwhile, heavy vehicles including 15-ton school buses and large trucks use the bridge regularly. Residents describe frequent center-line crossings and “close calls” with pedestrians.

A fatal crash on nearby Lincoln Road in 2002 underscored the risks on these narrow, winding approaches.

This context heavily influences perceptions of the current proposal: any change that widens the deck, strengthens the structure, or improves vehicle smoothness will, in residents’ view, inevitably increase speeds.

The 2024–2025 Proposal: Glulam Decking, Crash Barriers, and Modern Standards

The Joint Project Team (JPT) formed by Wayland and Sudbury, working with MassDOT, has proposed a rehabilitation that includes:

Replacing the timber deck with glued-laminated (“glulam”) timber panels

Installing crash-tested glulam barriers (TL-1 and TL-2)

Adding steel guardrail transitions on at least one approach

Maintaining a 5′ walkway

Providing a 20′ roadway between barriers

An initial plan included an asphalt overlay; this was withdrawn after unanimous public opposition.

The JPT argues that glulam is the only crash-tested timber system available for bridge barriers, and that modern standards require MASH-compliant transitions that currently exist only in steel.

But residents counter that:

Glulam decking is 12x more expensive per square foot than rough-sawn timber.

Asphalt or glulam would increase speeds and vehicle loads.

Glulam requires specialized fasteners installed from below, complicating maintenance.

No written MassDOT warning of imminent closure exists.

A 15 mph Traffic Safety Zone with advisory shoulders would achieve safety goals without compromising historic character.

They propose a simpler approach: replace the deck planks at an estimated cost of ~$100,000, patch and maintain the stringers, and reintroduce a 2½-ton limit and 15 mph zone.

An October 31, 2025 Letter to the Editor by Doug Stotz lays out board-foot calculations, material pricing, and a straightforward argument: the existing bridge can be replanked cheaply and last decades if speed and weight are controlled.

Legal, Regulatory, and Cultural Considerations

Residents and advocacy groups have raised questions about:

Historic obligations

The unrescinded 1971–72 agreement, MACRIS historic designations in 1987 and 1992, and the Priority Heritage Landscape status

Regulatory oversight

Because Sherman’s Bridge lies within a federally designated Wild & Scenic River, any work below the high-water mark likely requires a Section 7 Wild & Scenic Rivers Act review, which tests impacts on scenery, ecology, recreation, history, and literature (including Thoreau’s writings).

Residents argue the proposed design threatens at least four of these Outstandingly Remarkable Values.

State and local authority

Residents dispute the JPT’s claim that MassDOT “regulates speed limits on all public roadways,” citing: MGL c.90 §18 (local authority to set speeds on local roads), MGL c.90 §18B (20 mph safety zones), and Wayland bylaws giving the Select Board and Board of Public Works specific jurisdiction.

They also note Sudbury already posts a 20 mph limit on a comparable stretch of Lincoln Road.

Community Response: A Bridge with a Voice

Emails, letters, and public comments show an extraordinary degree of civic engagement. Themes include:

Preservation: “We’re not a throughway, we’re a neighborhood, a place.”

Safety: “The road isn’t wide enough to sustain the speeds people travel.”

Aesthetics: “Asphalt and steel destroy the experience of the bridge.”

Recreation: “Losing the boat launch would be a disastrous blow to the river.”

Heritage: “History lives under that narrow wooden bridge.”

Process: “The plan appears predetermined without real listening.”

Neighbor Jeff Stein wrote that Sherman’s Bridge is more than infrastructure: “Sherman’s Bridge IS a destination.”

Residents recall past fights over steel bridges, over power lines, over unannounced contracts and view the current proposal as part of a longer pattern requiring vigilance.

At a Crossroads: What Happens Next

The intermunicipal agreement currently sets 2027 as the end date for project completion, though it can be extended. Actual construction would require 3–6 months of closure.

But the more immediate decision is this: Which vision of Sherman’s Bridge will Wayland and Sudbury choose?

Option 1: A modern, crash-rated glulam structure meeting the highest vehicular standards, built with state-supported materials but requiring specialized future maintenance.

Option 2: A conservation-driven wooden replanking, combined with speed limits, weight limits, traffic safety zones, advisory shoulders, and historic consistency.

Option 3: A pause for deeper public engagement, new advisory committees, Select Board–led negotiations with 1971 successor owners, and a preservation-first review under historic and federal regulatory frameworks.

What is clear is that Sherman’s Bridge is not just a place where two towns meet. It is where Wayland and Sudbury must decide how they balance history, ecology, transportation, recreation, and identity. It is where 282 years of promise Indigenous, colonial, environmental, civic converge on one narrow wooden deck.

For nearly three centuries, Sherman’s Bridge has slowed travelers just long enough to notice where they are. What the towns choose now will determine whether that experience endures for the next generation or becomes the memory of a landscape that once felt timeless.