By Shea Schatell

Wayland Post Contributor

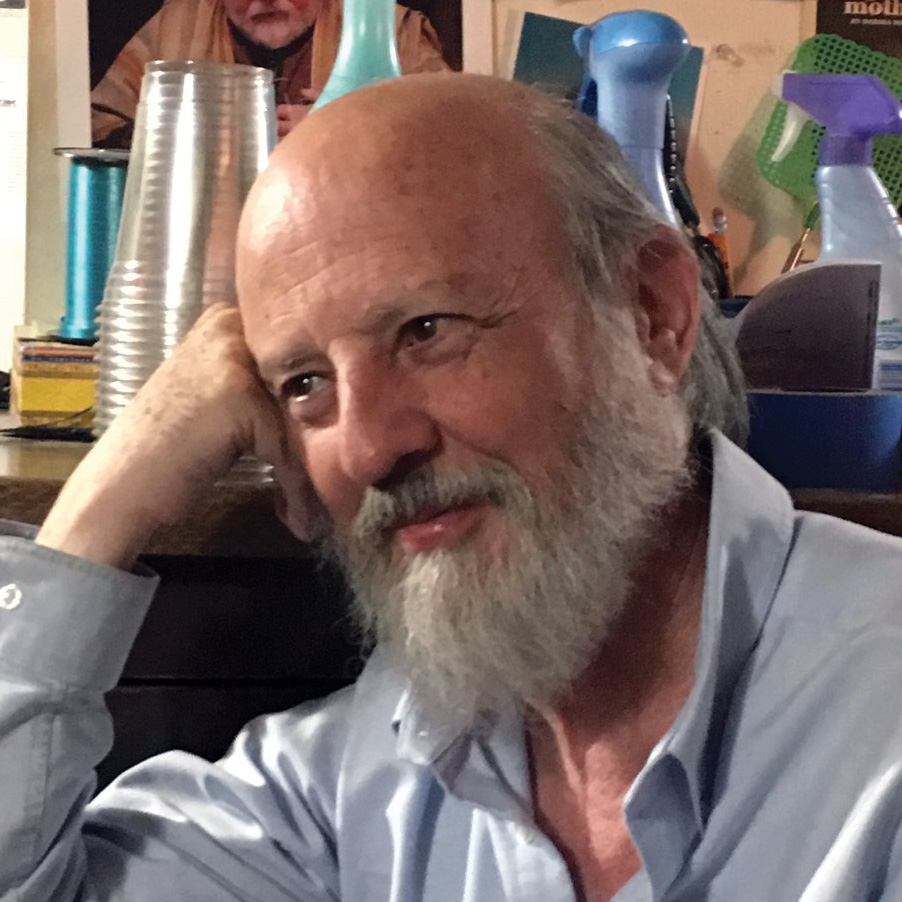

John Barrett has spent nearly half a century at the Vokes Theatre, yet he insists he is not the story.

For the longtime Curry College educator, actor, director, designer, and current president of the historic Vokes Theatre, the work has always mattered more than the person doing it.

“I like the hand of the director to be invisible,” Barrett said. “I don’t want people leaving a play thinking, ‘That was really well directed.’ I want them thinking about the story.”

Barrett’s connection to the Vokes Theatre began almost accidentally in 1979, when he reluctantly agreed to do a single community-theatre production. That show was ‘Charlie’s Aunt.” Forty-six years later, he is still there — now serving as president — having acted, directed, designed sets, built scenery, and helped shape the theatre’s culture.

His leadership philosophy mirrors his directing style. Barrett believes community theatres falter when power accumulates in too few hands. At Vokes, his goal is not control but stewardship. “My job is to keep the doors open,” he said, and to create a space where artists are trusted to do their work without interference.

Barrett grew up in Allston in a two-decker home, raised in what he describes as a “very ordinary Catholic, blue-collar” household. There was no dramatic awakening that pushed him toward the theatre. Instead, the pull felt instinctive. “It was innate,” he said. “It came from birth. I just always wanted to.”

Early mentors helped turn that instinct into discipline. At Boston College High School and later Boston College, Barrett encountered teachers who

emphasized stagecraft and rigor over theatrical mystique.

“They weren’t airy artists,” Barrett recalled. “They were focused on understanding the job and developing the skills.”

One of his mentors, Father Joseph Murry Larkin S.J., later officiated at Barrett’s wedding.

Barrett continued his studies at Catholic University, entering a highly competitive arts program, graduating with a master’s degree in Dramatic Literature. The experience reshaped his path. He pivoted toward teaching, but the road was long.

“I have a box somewhere of literally 200 rejection letters,” he said, describing nearly two decades of applying unsuccessfully for college teaching jobs.

In the meantime, Barrett built a working life in the arts through acting and writing. His acting career delivered moments of exhilaration and reality.

“My first job out of college was acting in a Shakespearean play with Al Pacino,” he often tells students. “My second was touring rural West Virginia with Ronald McDonald.” The contrast, he said, captures the unpredictable truth of the profession.

Writing became his financial anchor. A double major in theatre and English, Barrett spent many years working as an editorial consultant for the College Board. When he finally joined Curry College in 1997, he brought with him both artistic and practical experience, teaching theatre, writing, and stagecraft. Over time, he chaired the Communications department, believing that clear, purposeful writing would serve students well beyond graduation.

At Curry, Barrett insists that theatre education must be holistic.

“If you’re going to direct, you have to act,” he said. “You have to understand what actors are going through — and why it takes so long to hang a light.”

His approach reflects a lifelong belief that every role, onstage or off, deserves respect.

Outside the theatre, Barrett’s interests are as particular as his tastes in plays. He collects toy soldiers, reads biographies, follows the Tour de France, and tends rose gardens.

When asked what brings him the greatest pride, Barrett does not name a production. Instead, he speaks of former students who return years later to say that something he taught them made a lasting difference. For someone who prefers to remain invisible, it is a fitting legacy — not applause at curtain call, but the quiet endurance of craft passed on.