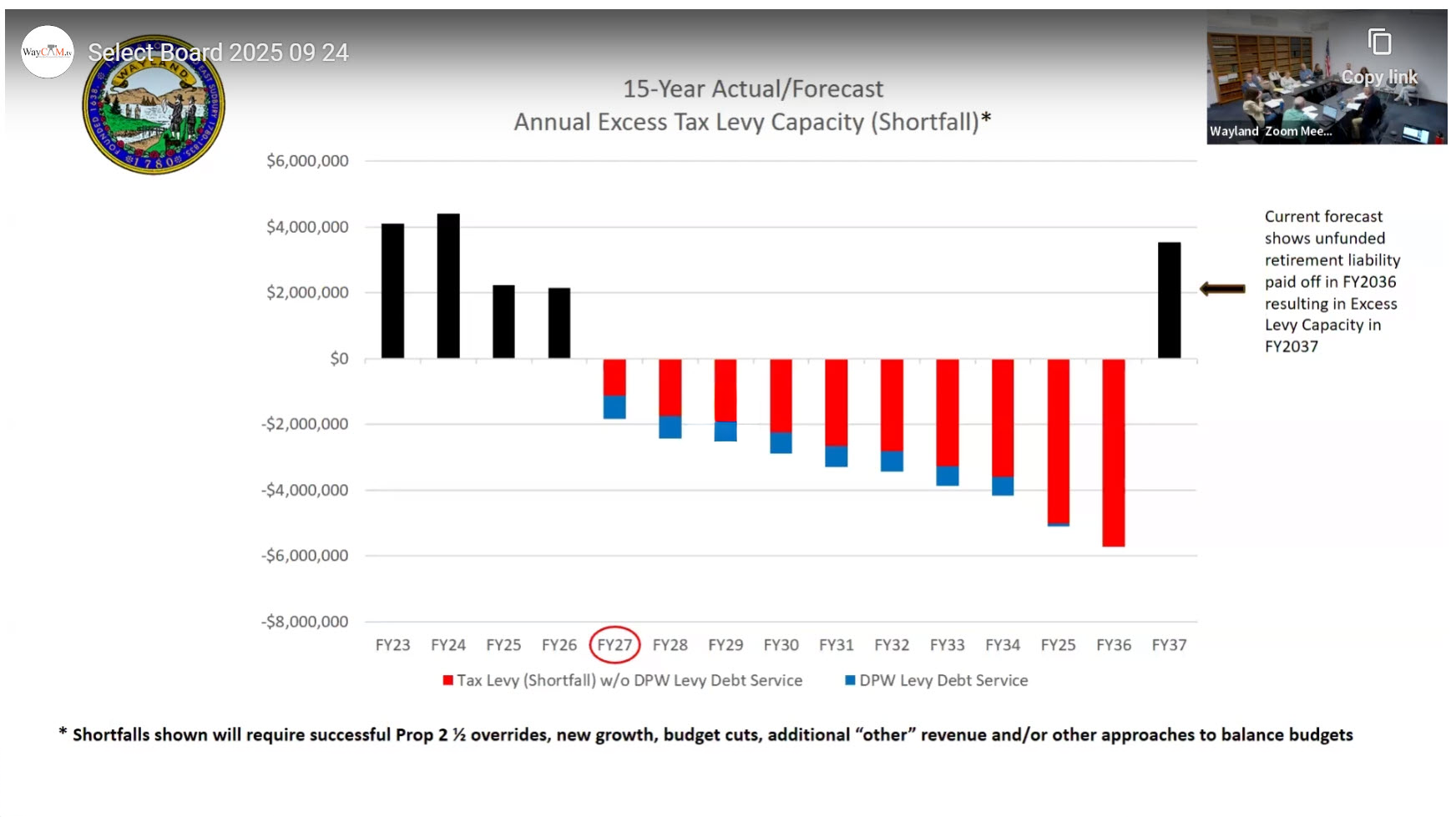

At the September 15 Select Board meeting, Finance Director Brian Keveny warned that Wayland’s fiscal problem is no longer cyclical. The town is sliding into what he called a structural deficit — a recurring mismatch between what the town can legally raise under Proposition 2½ and what it must spend on wages, benefits, pensions, insurance, and schools.

“We can balance FY27, but the structural deficit doesn’t go away,” Keveny said. “It comes back year after year, because the underlying cost drivers are fixed and increasing.” His 15-year financial forecast showed shortfalls almost every year from FY2027 until FY2036, when pension liabilities are finally retired and some breathing room returns.

Short-term fixes

For the FY2027 budget, Keveny outlined three tools to close an initial $1.9 million gap:

Shift $703,500 in debt service on the DPW building at 66 River Road from inside the levy to an excluded debt line.

Rely on short-term borrowing notes (BANs) instead of long-term bonds, saving about $802,500 in that year’s budget.

Cut $300,000 to $500,000 in services.

These moves narrow the deficit enough to balance FY27, but Keveny cautioned they are temporary fixes that keep the town afloat for one year but do not address the structural imbalance. “Beginning in FY28, we will need a long-term solution,” he warned.

Two buckets, one well

One reason the gap persists is the way Wayland’s budget is structured. Both town and schools draw from the same levy — two buckets dipped into one well — but the school side dominates.

FY2025 year-over-year school budget growth: $2.6 million (3.4%).

FY2026 projection: $4.2 million (6.1%).

Long-term trend: annual school increases averaging 5–6%, compared to general inflation under 3%.

“Without corrective action, we face a structural deficit of at least $3 million by FY2027,” Keveny said. “That number assumes level services and no surprises in health insurance or special education.”

Local receipts, such as motor vehicle excise and building permits, are projected to remain flat. State aid is growing only marginally, at less than 2% per year.

For years the town has trimmed their departmental budget to help balance the overall budget. But the imbalance is clear: the education bucket is far larger, and each year it pulls more from the well.

According to the FY2026 warrant materials, the School Department accounts for just over half of Wayland’s operating budget, while town departments and unclassified costs make up the remainder.

Schools: about $53.3 million, representing approximately 52–53% of the general fund operating budget.

Town departments: about $25 million, or approximately 25%.

Unclassified costs (insurance, pensions, utilities, and debt service): about $28.8 million, or approximately 22–23%.

This breakdown shows the structural imbalance that Finance Director Brian Keveny emphasized — the education budget dominates the levy, with 83–85% of school spending tied to labor, leaving far less flexibility on the municipal side.

This has been the story in Wayland for decades. Every time an override looms, residents argue whether cuts should come from classrooms or town services. Keveny’s forecast shows that this familiar debate will only intensify.

Triple wave of capital costs

In addition to the current structural deficit, a second surge is rising: a set of massive capital projects that together form a triple wave of looming capital obligations.

The proposed MWRA water connection and PFAS treatment system carries a price tag of $38.6 million; if funded through property taxes, would add roughly $950 to $1,100 per household each year, while financing it entirely through water rates could drive residential bills up by 30 to 70 percent.

On top of that, state-mandated lead pipe replacement is estimated at $5 to $10 million, with a $10 million program translating to about $250 per household annually. Not included are possible costs to homeowners whose homes are directly connected by a lead service line.

The third and largest obligation is school facilities, where options range from major renovations to new construction costing $50 million to $100 million. A $50 million debt exclusion would mean an additional $1,250 per household per year, while a $100 million project could add more than $2,500 annually.

Keveny’s presentation showed that if these projects overlap in timing, the average household tax bill could increase by $2,500 to $3,000 a year estimated on top of the usual levy growth allowed under Proposition 2½.

The ceiling above

All of this takes place under the 2½ ceiling. Proposition 2½ caps the annual increase in property taxes at 2.5% plus new growth, unless voters agree to break through with an override or debt exclusion. Wayland’s position is especially constrained. With new growth at just 0.66% of the levy — ranking 312th out of 365 towns — and more than 90% of revenues coming from residential property taxes, there is little commercial cushion. Every time an override or exclusion is approved, the burden falls almost entirely on homeowners.

Behind the numbers lie two forces: the education engine and the shadow costs.

Education is the driving engine of the municipal budget. Because schools account for the largest share (and most of that spending is tied to personnel), annual growth in salaries and benefits pulls the entire budget forward. When that engine accelerates, whether from contract settlements, special education demands or rising health insurance costs, the rest of the municipal “train” is forced to keep pace.

The shadow indirect costs are harder to see but no less real. Pension liabilities, though scheduled for payoff by FY37, consume levy space each year. OPEB costs (other post-employment benefits like retiree health insurance) run decades into the future. These obligations accumulate offstage, but they dictate how much money is left for schools, fire trucks and playgrounds. As the Town continues to hire more people, exposure increases.

Toward a blueprint

Keveny’s forecast offers one moment of relief: FY 2037. That year, when old pension liabilities are finally retired, the deficit disappears and capacity returns. Some call this the 2037 horizon. But that’s 12 years away, and as Keveny said, “the problem doesn’t go away.” He and the Massachusetts Division of Local Services suggest a blueprint that moves beyond short-term patches. That blueprint would likely include:

A multi-year operating override, permanently raising the levy base.

Reassessment of labor and contract obligations, especially in schools where costs are most concentrated.

Disciplined capital planning, phasing projects and maximizing state/federal reimbursements.

New revenue sources: local option excises, fees, grants, and nonprofit agreements.

Strengthened financial policies on reserves, debt, and overlays, to reassure rating agencies and maintain the AAA bond rating.

The choice, Keveny suggested, is not whether to pay but how — and how much at once. “These are tools to get us through FY27,” he said of the temporary fixes. “They do not change the structural reality. Beginning in FY28, we will need a long-term solution.”

One official put it bluntly: Wayland is at an inflection point — an identity crisis as much as a fiscal one. We can keep patching the budget with debt shifts and short-term fixes and hope to limp along until 2037, or we can face reality and adopt a blueprint that means permanent overrides, stricter policies, and tough choices on labor and benefits. The real question is whether Wayland wants to become more like Weston or Wellesley, with higher taxes supporting first-class services, or hold on to its mixed character with a tighter budget.